Adviser:KUANG-KUO CHANG(章光國)

By I-TING SHIH(施怡婷), HUI-YU CHENG(張惠瑜), WANG-LING TSAI (蔡宛玲), YUN-CHEN YANG(楊昀蓁)

Parents and Teachers Share Responsibilities to Curb Childhood Obesity

Cheng-Chien hastily packed his stuff—a meal bag, a cram bag, and a cup of bubble tea—and rushed to his next destination, a cram school two blocks away the moment the class bell rang.

Cheng, a 13-year-old student at Da-Jou Junior High School in Kaohsiung, spends every weeknight attending cram school where he usually has hamburgers or fried noodles for dinner.

The school boy’s study routine is a typical reflection of Taiwan’s teens and younger. What might not be so typical is that he is obese.

On weekends, Cheng, now weighed at 70 kilograms, plays badminton and basketball with his father at a park nearby his home, and he occasionally rides a bicycle around town. Although being obese, he still spends quite some time watching TV, playing mobile phones, and playing puzzle games.

The Foundation for Cancer Care in Taipei conducted a dinner diet survey of elementary school students (from the third to sixth grade) in Taiwan’s four largest metropolitans—Taipei, New Taipei City, Hsinchu and Kaohsiung. More surprisingly some 16 percent dine out every day, the survey data suggest.

This kind of dining habit and life style has contributed to the growing problem of obesity for an increasing number of Taiwan’s schoolchildren. Foods served by street vendors or low-cost restaurants usually are deficient of fruits and vegetables but high in salt, sugar and calorie.

Rong-Hong Xie, a professor of nutrition and health sciences at Taipei Medical University, said that childhood obesity worldwide is due essentially to unbalanced caloric intakes and outtakes—eating too much but exercising too little.

According to the World Health Organization’s most recent data, 42 million children under the age of 5 were overweight or obese in 2013. Once considered a high-income country problem, overweight and obesity are now on the rise in low- and middle-income countries. Domestically, the Ministry of Education reported in 2015 that 28.1 percent of primary school students and 29.5 percent of those in secondary schools are overweight or obese.

Xie said genetic makeup, formed in the stage of embryo and breastfeeding, is another factor for the growing problem in obesity. And obese mothers normally rear like offspring in part because they serve as a bad role model for their kids. As a result, Xie emphasized that childhood obesity is due in part to bad parenting.

Shou-Jyun Wong, a third-grader of Taipei’s Jian-An Elementary School, faces a somewhat similar problem as does Chang.

“I really don’t like the school lunches. I always admire my classmates who have a family-prepared lunch meal,” said Shou-Jyun.

He said his schoolmates often complained that the school lunch food is too greasy, monotonous, and not hygiene.

The 9-year-older pointed out that fruits are offered only once a week, with daily menu barely changed. He complained further that his teacher also demands students not waste food, forcing them sometimes to eat more than they can.

However, how to eat in a healthy manner is not an easy task. “No one has taught our children how dining out will affect their health. The teachers and parents just urged children not to eat certain unhealthy food, but never explains to them why,” said Fendi Fan, CEO of Mini Cook which is a studio for promoting diet education.

“In other words, if they don’t truly understand the ill results from eating unhealthy food, they would not care about what they eat,” she continued.

Weight Watch Programs Untracked

In recent years, an increasing number of elementary and junior-high schools have organized health camps or seminars for overweight students as a response to the surging advocacy of the Ministry of Education on weight watch.

Nonetheless, Cheng’s mother, Mei-Chun Chen, whined about the program’s uselessness, adding that his seventh-grader son is now classified as obese with a BMI about 35.

She said that Chang in his sixth grade once participated in a weight reduction workshop organized by his former primary school. Participants in the one-year project merely spent one to two hours weekly on exercising aerobics or attending speeches. She complained that the light-weight, superficial program not only failed to help his obese son cut weights but instead further pump up more kilograms.

A similar health camp is in operation at Taipei’s Ming-Chuan Elementary School, designated and counseled by the nutritionists from the Cathay General Hospital.

In the first week, participating overweight children got to learn about the amount of sugar contained in their favorite drinks by conducting a fun experiment on beverage ingredients. In the following week, they talked about the choice and impact of dining out, and they learned how to make high-fiber desserts on their own in the final week of the program.

But a notable drawback of the workshop exists. The school failed to track participants’ weight changes afterwards, so its effectiveness remains to be seen.

Jing-Yi Pan, section chief of hygiene of the primary school, explained that her school has no extra funding for monitoring in that the operation of the free camp is completely funded by government. She added that participation may drop if funding is cut and parents are unwilling to share the cost.

The reason such in-school health programs often fail is that school health education is knowledge-based, instead of behavior-driven, according to Xie, and as a result, it is very difficult to alter school children’s diet preferences.

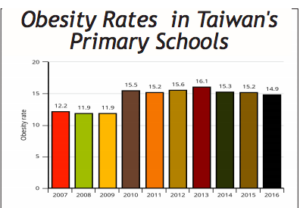

However, he said, “Childhood obesity has seemed to be in gradual decline the last two or three years. And parents, not school teachers, bear the greatest responsibility for the problem.”

Fan shared with Xie’s points of view. She stressed that parents have to help their children build a healthy lifestyle, encouraging them to exercise more and eat more nutritiously.

But helping the youth to develop and sustain a good diet habit isn’t effortless. Both parents and teachers need to acquaint themselves with the so-called “diet education” that covers topics ranging from food safety and food nutrition to food culture.

“Actually, the school diet education in Taiwan isn’t better than any other countries simply because virtually all of our teachers have never heard of the diet education,” Fan pointed out. “Therefore, instead of expecting teachers to educate children about diets, parents shall learn it and help their own children to maintain healthy diet habits.”

In addition, Fan intends to underscore what has long been overlooked by the official diet education. But her efforts have been stonewalled by schools where she has visited to promote her ideas. To overcome this barrier, she has decided to bring this new practice to legislation, in an effort to garner the attention and support of lawmakers and the public.

Fan said, “Children have a right to know about how unhealthy diet can undermine their health. If these youths know that drinking too much sugar-rich beverages can lead to diabetes, cardiovascular diseases and cancers, they would think twice before pulling money out of their pocket.”

Childhood Obesity shows Urban-Rural Division

Xie said there exists a noticeable gap between the urban and rural areas with respect to childhood obesity, adding that diet habits usually are forged at the kindergarten stage. He said parents living in Taipei City, New Taipei City and Hsinchu County are much more attentive to their children’s diets than are those in the other cities.

This disparity, Xie pointed out, is due largely to the varying types of family structure in Taiwan. More families and households in the other regions are constituted with grandparents and foreign spouses.

Such family normally is in a lower socioeconomic status, failing to obtain necessary nutritional information concerning children’s health, thus becoming unknowledgeable of healthy diets. Lack of time or wealth forces these grandparents or foreign spouses to feed their kids with convenient or nutrition-poor food, such as fast food and fried food.

The primary school the third-grader Shou-Jyun enrolled at is considered an elite program in Taipei City. Institutions like his are known for their education development and attract pupils from wealthy family. Most of the parents are well educated, capable of nurturing their children’s physical and mental health. The little schoolboy has dinner with his parents virtually on a daily basis, with a variety of food full of nutrients that most youths from the lower-income family cannot afford.

However, despite of the financial advantage enjoyed by children like Shou-Jyun, the academic pressures they face force them to study and stay late. Cut hours for sleeping and exercising can likewise result in overweight. .

Shou-Jyun said he usually went to bed around midnight and therefore often dozed off during classes, adding that he hopes to do some exercises on weekends but only if time avails.