Reporter/Yang Chen-Jui

A rough-toothed dolphin lay motionless at the bottom of an artificial pool, its life hanging by a thread as water lapped at its mouth. Guo Xiang-Xia directed rescue volunteers to regularly pour water on the injured to keep its skin moist, carefully observing its health condition.

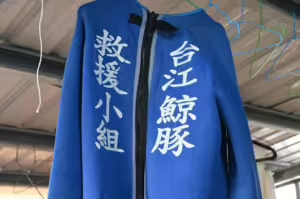

Guo, a senior stranding response specialist of the Taiwan Cetacean Society (TCS), and his colleagues were notified of the sea mammal’s stranding at a beach in New Taipei’s Bali District in the afternoon on Sept. 7, 2023. They soon arrived and transported the creature to the Badouzi Rescue Station for preliminary injury assessment.

After completing several examinations the next day, they found synthetic linear objects in the dolphin’s liver and digestive system, causing infections and digestive issues.

The rescue team promptly arranged for an endoscopic examination of the digestive tract, after which the medical team decided to increase the supply of nutrients and calories while administering antibiotics to control the infection.

Despite the team’s effort, the rough-toothed dolphin died after a week from sepsis.

Over the past five years, Taiwan has witnessed over a hundred cetacean strandings annually—averaging once every three days—with most involving dolphins struggling to breathe.

However, as experts pointed out, the phenomenon reflected not only a potential deterioration of Taiwan’s sea environment but more significantly, its people’s long-term negligence of their responsibility to their sea neighbors as island country citizens.

Human threats

According to a report from the National Museum of Marine Science and Technology, cetaceans tend to inhabit and forage in productive marine environments.

The abundant fish resources brought by the Kuroshio Current are likely the reason for the 32 cetacean species, or about one-third of the total number around the world, that appear along Taiwan’s eastern coast.

These creatures have been under conservation efforts in Taiwan since 1990, with all dolphins and whales being listed for protection in alignment with global trends and to address international pressures.

However, according to data from the Ocean Conservation Administration (OCA), the number of strandings along the coast of Taiwan has risen in recent years. Between 2018 and 2023, the average number of stranding cases reached 149 per year, marking an increase of nearly 60 percent compared to the average before 2018.

Cetacean strandings in Taiwan are mainly attributed to three causes: bycatch in fishing activities, vessel collisions, and physiological diseases, a TCS report indicated.

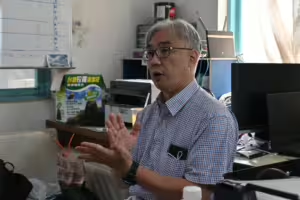

“There is a growing correlation between strandings and activities such as fishing and frequent maritime traffic,” said Yang Wei-Cheng, a professor from the College of Veterinary Medicine at National Taiwan University.

The maritime traffic has rendered these sea mammals more vulnerable to vessel collisions or propeller strikes, given that the routes of industries like fisheries, trade and tourism often overlap with their migration routes.

Besides, post-mortem examinations of stranded cetaceans frequently reveal anomalies in their respiratory, liver, and immune systems.

Guo highlights the clash between Taiwan’s industrial growth and marine conservation: “We must ask ourselves, should it be humans or cetaceans that change their direction?”

He believes that cetacean rescue efforts serve as a declaration of conservation, conservationists must advocate for the protection of these marine animals who cannot speak for themselves.

Conservation ≠ Rescue

People tend to see rescue as a synonym for conservation, but Yang said that conception is not accurate.

While the ultimate goal of conservation is to ensure species survival, rescue action refers to one part of cetacean conservation, advancing research through the efforts to enhance conservation environments, said Yang, who referred to cetacean rescue as “more than saving dolphins and whales.”

“We get to learn what occurs in the ocean through [cetacean rescue]… You’re not doing cetacean rescue but another humanitarian work if your task stops at saving an individual’s life.”

Cetaucean rescue requires the staff not only to save an individual but also to learn what the group it belongs to has experienced, Yang said.

These efforts are used to analyze population status, serving as a crucial step in conservation efforts and an important initiative.

Yet, due to the slow process of conservation research, the government has shown little interest in supporting long-term research, Wang said.

Marine lives matter

Wang said many people wonder why, given the vastness of the ocean, the focus is on cetacean conservation.

He explained that observing and studying the ocean’s conditions is challenging, but cetaceans, being mammals, frequently surface to breathe. This characteristic makes them easier for humans to monitor.

Additionally, since some cetaceans occupy the top or middle levels of the marine food chain, observing their populations can help assess the health of the marine food web and ensure the ecology’s well-being.

Wang also added that over the past few centuries, extensive whaling and the misuse of marine resources have led to a dramatic decline in the global whale population, with some species nearing extinction.

From a scientific perspective, most cetaceans have low reproductive rates, typically bearing only one offspring at a time, and many species have parental care periods lasting 2-3 years. Therefore, if cetacean populations experience a sudden decline, the risk of extinction would become significantly high.

In addition, Wang stated that one of the issues hindering conservation progress in Taiwan is the long-standing neglect of marine issues by its people.

In recent years, the Taiwanese government has been promoting offshore wind energy development to pursue green industry, but scholars have found that noises and low-frequency sounds from these constructions can lead to cetacean hearing damage, strandings and even death.

Guo said he does not oppose the development of offshore wind energy because “the entire Taiwanese economy will collapse otherwise,” but “we must first find an alternative way to save these dolphins.”

Meanwhile, Wang argued that Taiwanese people’s long-term ignorance of their citizenship of an island country should result from the passive governance of past administrations.

During Taiwan’s martial law period from 1949 to 1987, the government implemented strict regulations restricting public access to coastal areas. Most of the coastline was closed off, and only local residents were permitted to engage in fishing-related activities.

Even after the martial law period ended, subsequent governments continued to neglect maritime culture, weakening the connection between the Taiwanese people and the surrounding waters of their homeland, he said.

Encore

OCA’s records show that the survival rate of stranded cetaceans used to stand under 10 percent before 2020. That rather low figure, according to Yang, resulted from the fact that cetaceans, unlike humans, cannot seek medical treatment when they fall ill.

This sees most of the stranded whales and dolphins close to “a patient in critical condition” when they are spotted, he explained.

Thanks to the integration of manpower and upgraded medical facilities by OCA, the current survival rate has improved to 30-40 percent in the past three years since 2019 when dedicated handling of stranding cases began.

However, the TCS and other conservationists like Wang urge the public not to judge the successfulness of rescue efforts solely based on whether or not the whales and dolphins are released back into the ocean, as that is only one of several options.

“Every stranding case resulting in death is not defeated, all of it could serve as a silk thread to the rescue web, contributing its value to advance cetacean conservation efforts,” Wang said.

He likened conservation work to running a relay race, emphasizing that the path of doing the right thing and advocating for conservation has no end.

Just as Yang wrote in a Facebook post to encourage others after the rough-toothed dolphin passed away last September: “Death is not the end, but another beginning for continued investigation.”